Cloud hiding undersea: Cables & Data Centers in the Mediterranean crossroads

Paper for the Commons & P2P Observatory of Alternative Policies Institute, 21 January 2025

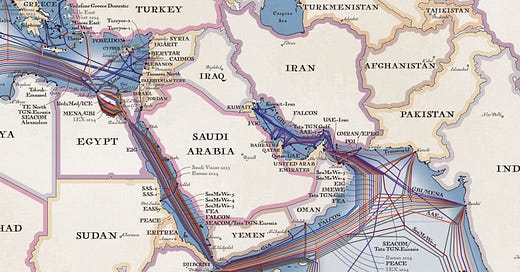

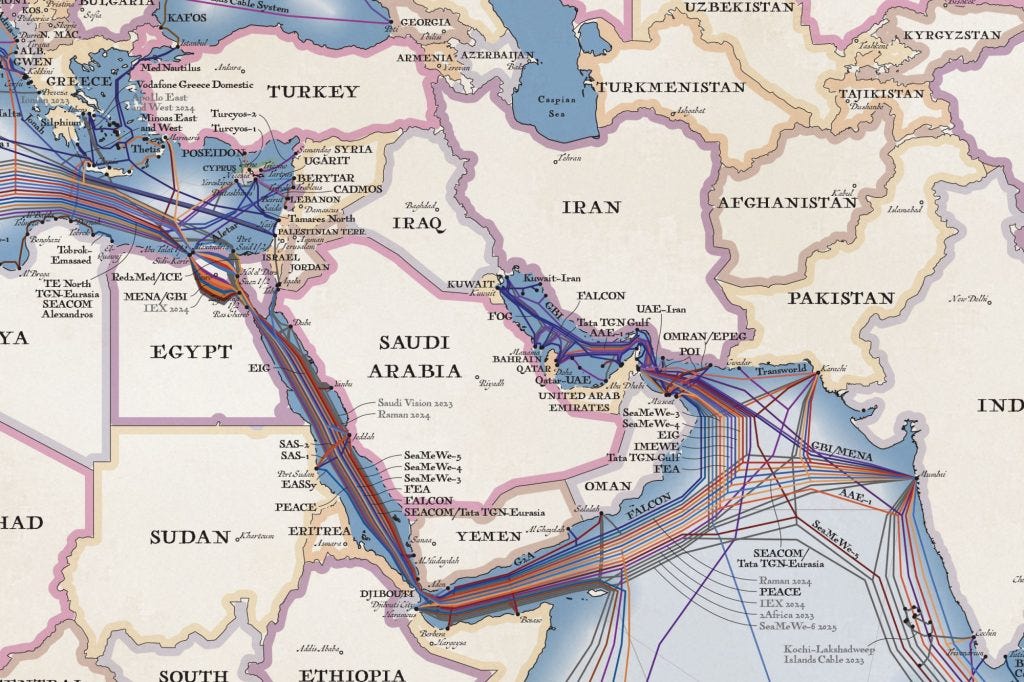

The maturity of a digital economy can be quantified based on how much internet content is cached and distributed locally (1). For instance, most African nations —apart from South Africa and more recently Nigeria and Kenya— continue to look to Europe for internet content. This leads to high latency and increased transport costs, which inhibit internet adoption and use. As new applications become more data-hungry, the importance of keeping traffic closer to home and improving affordability for end users will only continue to grow. Greece, due to its geographical location, plays the role of an alternative route for Eastern Europe. It is the shortest route to the interconnection with the markets of the Middle East and Asia, as well as Africa. The underwater fibre optic cables in the Greek area pass through Piraeus and Chania and cross for kilometres the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, joining the network of Greece with that of Israel, Cyprus, Turkey and Italy.

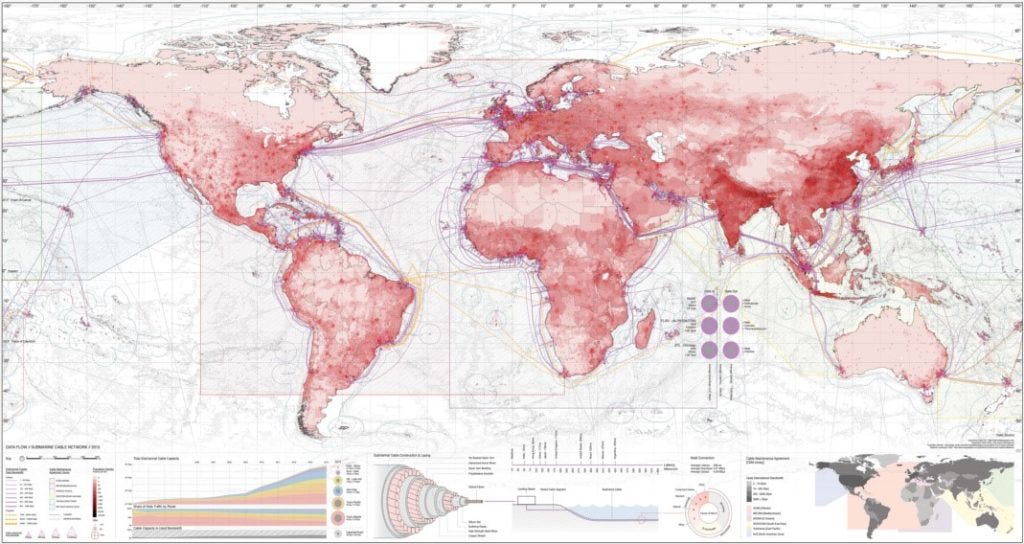

Digital transformation brought the need for distribution in Data Centers’ locations and augmented the importance of massive sub sea cable networks. The Mediterranean enables global connectivity due to the prime geographic position that occupies between developed markets and new emerging markets and support the digital economies of three different continents (image 1).

While Marseilles has historically been the busiest sub-sea cables destination in Southern Europe, operators of the latest cable systems are seeking diversity of landing sites along the North Mediterranean coastline for many reasons, including improved resiliency in the event of force majeure or international incidents – not to mention significantly decreased latency by providing a more direct route. At the same time there is a growing strategic significance on the seabed since the primary instruments of the cyber warfare threat to undersea cables are sabotage. The goal could be financial harm on companies, cyberattacks, or interference with vital intelligence networks. The Mediterranean Sea’s undersea cables are a vital target for potential adversaries, as it is a key node in the global communication network.

Telecommunications technology has come a long way in the last 150 years, but the one constant throughout has been the humble sub-sea cable. It is cable systems, not satellites, that transport most of the Internet around the world. Today, about 99% of all transoceanic digital communications crosses through undersea fiber-optic cables (2). A huge ecosystem through which $10 trillion worth of financial transactions are conducted every day on ever-more complicated supply chains. A sizable industry that is projected to increase by 12.9% between 2022 and 2030, reaching a value of $48 billion (3).

We can imagine a future were sub-sea cable systems dedicated to data transmission and green energy supply to data centres will continuously transform the Mediterranean bed sea. High-voltage power cables, connected to offshore wind farms are part of that systems. Though necessary for worldwide energy supply, the installation and operation of these global communication infrastructures has sparked many concerns about the potential environmental impact, the economic issues arising from complex fisheries management, and the need for sustainable policies and regulatory changes to prevent a cyber-war on the seabed. They’re usually buried beneath the seafloor for protection as they carry large currents of concentrated electricity. That type of construction concerning the Mediterranean, affect on its way possible Posidonia oceanic meadow (4). Their placement can disturb the marine ecosystem by generating electromagnetic fields. It mainly affects the navigation of electrosensitive marine species, such as sharks and even eels, who use their internal magnetic north sense to prey and orientate. Telecommunication cables do have an impact in terms of electromagnetic field disturbance for sea creatures, but this is a minimal or even benign footprint on the marine environment.

The cost of a single cable in the submarine cable sector can reach hundreds of millions of dollars, depended on the route’s complexity and length. The “private owner” model, where a single IT corporation owns and operates the cable for its own purposes, has recently become more prevalent, although the “consortia” one – between telecommunications, large technology businesses, and infrastructure specialized companies – has always been looked upon favourably. Collectively holding more than 66% of the submarine cable network’s capacity, submarine cable routes are being redesigned by these companies to connect their Data Centers in order to scale up digital production and storage (5). Content providers such as Google and Microsoft are increasingly major investors in new cables. According to the relevant international conventions, the law of the sea and common sense, the sea bed is under the status of ‘Common Heritage of Humanity’. However, that type of infrastructure is owned and created by private companies that are acting underneath the sea surface into a blur and inadequate regulatory framework.

The importance of infrastructures

In addition to Data Centres the internet consists of vast infrastructures that include underwater, underground and above-ground cables, optical fibres, satellites and their ground stations, cable signal boosters, and a host of others. A cable network is an assemblage of many technologies, including the cables themselves, the ships that lay them and the submerged repeaters that boost signals on the ocean floor. The above are fields of conflict between public and private interests and have a strong material footprint given the volume of resources they consume.

In a way we can refer to them as spaces that appeared faster than our ability to perceive what they represent, mainly in terms of the system of values they embed. The current phase of capitalist development manifests itself through a very diverse range of spatial byproducts: Data Centres, warehouses, container terminals, logistics parks, and many others. Internet infrastructures fall into that category as they express specific power relations, exacerbate issues of labour, and generate dramatic processes of subjectivity. According to the architect St. Corbo they constitute new forms of urbanity in absence of the traditional city, interrelated to their physical and symbolic role as interface due to its ambiguous condition of being at the same time local and global, isolated and connected, compressed and expanded (6).

However, is the narrative of the cloud – an immaterial and virtual internet – that dominates our collective imagination. Only recently the relative literature has focused on the construction of insulating narratives and the ‘hiding’ process that is accompanying the Data Centres industry and relevant infrastructures. N. Starosielski has focused on those narratives regarding optical fibre networks, studying the distorting effect of their transformation into invisible and repulsive infrastructures (7). The aim of that transformation is the protection of the cables from any threat (regulation, protests, boycotts, nearby environment). Insular narratives constitute limited descriptions of the visual network, presenting it as a technological network that facilitates our online contacts, ignoring its interaction with the environment, local societies and the human factor. On the contrary, the contribution of investments to the national budget and to the upgrading of the role of each country as an international data hub is highlighted. To a certain extent, the facilities are dematerialized, leaving visible only the service they offer.

The main reasons are related to the environmental consequences of Data Centres, the data ownership status and the eligibility of those processes. For example, Data Centres located in Ireland are expected to consume 1/3 of the country’s total available energy by 2027. On a global scale Data Centres are more than 9 million and are responsible for approximately 3% of global energy consumption and 2% of global carbon emissions (8). There are many occasions where local communities rose up and kicked Data Centres out of their area or demanded regulations for their protection.

In the same time, data production, storage and above all ownership status is of extreme importance for value production and strategic planning. For big players, it is crucial to store data in a secure and cost-effective way that assures monopoly access. A glance at the ‘terms & conditions’ of big digital platforms -which we accept by necessity – usually reveals clauses allowing for use, trade and storage of data in jurisdictions different than the users’ home countries. A multitude of actors, organizations, movements active in the fields of consumer and digital rights oppose unregulated cross border data transfer. Civil society actors point out that unregulated cross border data flow could undermine the right to privacy and data protection.

The term cloud acts as an insulator for Data Centers, data transfer and their infrastructure, such as submarine cables. Any appearance of the infrastructure is equivalent to exposure to possible unexpected developments. The universal prevalence of this narrative leaves internet providers undisturbed and unregulated to develop it for the sake of profit and the consolidation of their power. The cloud constitutes a cryptic narrative that reassures internet users by hiding the repositories of their secrets which now belong to the providers with the consent of the former (9).

Changing the perspective by describing the material terms of the internet (which is ultimately more wired than wireless, semi-centralized than distributed, territorially grounded rather than territorialized, precarious rather than resilient) could favor parameters linked to human rights and environmental protection (10). Today, few people know where these infrastructures are located, how large their facilities are, as well as their effects in terms of energy and water consumption, their geostrategic implications or the regulation applied to the ownership, processing and transfer of user’s data. Little is known about the substations, the ships laying cables on the seabed, the abandoned optical network infrastructure and the local communities that surround all of the above. The infrastructures that are under the sea are covered by an additional veil that keeps their presence hidden, while at the same time the underwater space is treated as an unregulated privileged space for the expansion of internet infrastructures.

* Theodora Kotsaka researcher and writer, is a political scientist and works on commons and digital transformation for think tanks and research institutes. She has been a scientific advisor on relevant policies for Ministries and the Greek Parliament and collaborates with privet sector as an expert for research projects. Since 2019 she is Co-ordinator of the Observatory on Commons and P2P Production (Institute of Alternative Policies, ENA). Her current work focus on knowledge commons and digital transformation. Her work has been published in monographies, press, journals, and collective editions.

Martin Atkinson & Nick Portch, “New Subsea Cables Make the Mediterranean a Global Digital Crossroads”, 12 April 2023. https://blog.equinix.com/blog/2023/04/12/new-subsea-cables-make-the-mediterranean-a-global-digital-crossroads/.

Nick Routley, Map: The World’s Network of Submarine Cables, 24 Augoust 2017, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/submarine-cables/.

Michele Calamaio, “How Submarine Cables are Threatening the Fragile Ecosystem of the Mediterranean Seabed”, 14 December 2023, https://earthjournalism.net/stories/how-submarine-cables-are-threatening-the-fragile-ecosystem-of-the-mediterranean-seabedhttps://earthjournalism.net/stories/how-submarine-cables-are-threatening-the-fragile-ecosystem-of-the-mediterranean-seabed.

op. cit.

Alan Mauldin, A (Refreshed) List of Content Providers’ Submarine Cable Holdings, 27 June 2024.

Stefano Corbo, “Exteriorless Architecture Form, Space and Urbanities of Neoliberalism”, London Routledge, 2023, p.75.

Nikole Starosielski, “The Undersea Network”, Durham, London Duke University Press, 2015. Starosielski created the website www.surfacing.in where detailed maps of undersea cables and their accompanying narratives are presented.

Monika Domman, Hannes Rickli, Max Stadler, “Data Centers: Edges of a Wired Nation”, Zurich Lars Muller Publishers, 2020, p.17.

G. Mpougioukos, “Touching the cloud: exploring the material conditions of Data Centers”, NTUA Diploma Thesis, 2024 (in Greek).

Nikole Starosielski, op. cit., p.10.